Bigger than Brexit: Europe's ageing population, migration and the impact on economic growth

The second in a series of blogs by Neil McLocklin, Partner in Knight Frank's Strategic Consulting team, focussing on the fundamental changes that are occurring across Europe and the challenges that businesses face in this fast-paced, competitive and above all uncertain climate.

9 minutes to read

Following my blog on 10 Significant Winds of Change that impact business location decisions in Europe, I will now focus on each point in more detail, examining how population growth or decline and migration impacts world economies, globalisation and business activity on both macro and micro scale.

Demographics

Demographic changes are critically important; the strongest correlation in economics is between population growth and GDP growth. If you have any doubt about the impact of population growth or decline on the economy, business and the derived demand that drives the value of real estate I would suggest a visit to Armenia, a country where the population has fallen by nearly 30% since 1991 and where you cannot give away commercial property.

Without population growth countries must rely upon productivity improvement, which would appear to be a challenge globally for many developed countries. Focusing on demographics, there are three big challenges facing the big economies around the globe to different degrees - birth rate, an ageing population and economic migration. Another challenge that is redistributing population within economies is the rise of cities and the decline of smaller towns and rural areas. Let’s dive into each area:

Falling birth rate

A declining birth rate in many larger developed countries is a significant concern. It has the potential to stall long-term global economic growth and cause major issues in countries with low birth rates.

To be at a sustainable level, a country typically needs two children per woman. Of the G7 economies, three countries are significantly below this level – Germany, Italy and Japan - all at 1.4.

Canada is at 1.6 whilst the other three G7 economies have more sustainable levels but are in gradual decline – UK (1.9), US (1.9), and France (2.1).

There are various cultural, economic and social reasons why birth-rates in developed countries are in decline and the impact is not easy to address. Germany has tried various social and economic incentives to arrest the decline in part, opening its borders to 1 million refugees to reboot population growth.

This population influx has actually resulted in the first increase in birth rate in the country but sustaining it is a different matter.

Japan has the world's quickest ageing population globally

Ever increasing economic migration

Migration is one of the most politically sensitive topics in many of the developed countries in the world. Scenes of refugees risking their lives crossing the Mediterranean as they seek asylum in Europe feature heavily in the news on a weekly basis.

Similar mass political migration is taking happening across Asia where The United Nations Refugee Agency estimates there are 3.5m people seeking asylum, largely from Afghanistan and Myanmar.

Whilst the hardship of the people seeking refuge from war and political persecution is heart-rending, in overall number terms globally it is relatively small compared with economic migration.

The number of people living outside of their home countries in 2015 due to economic migration stood at 243 million (3.3% of the world’s population), whilst refugees accounted for less than 20m. In 2015, two-thirds (67%) of all international migrants were living in just 20 countries.

The largest number of international migrants (47m) resides in the United States of America, equal to about a fifth (19%) of the world’s total.

Germany and the Russian Federation host the second and third largest numbers of migrants worldwide (12m each), followed by Saudi Arabia (10m) and the United Kingdom (nearly nine million). Economic migration was one of the significant driving forces behind some of the political shocks of 2016, notably Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, as well as the rise of right wing parties across Europe and further afield.

On the other side of the coin, we are also seeing very significant population declines in many countries in Eastern Europe, the Caribbean and Pacific driven largely by economic migration.

Poland, the sixth largest country by population in Europe (38 million), has been struggling with a declining population for more than 20 years, due to both low birth rate and emigration. In the first 10 years of EU membership, 2 million Poles left the country resultant in birth rate decline to below 1.3. Poland’s population is set to reduce by 5.3m by 2050 according to its government, if no preventive measures are put in place.

Incentives for women to produce more children have in large part been successful - but this has has an unforeseen economic and social knock-on effect as mothers have left the workforce. It demonstrates the challenges of maintaining a sustainable and productive labour market.

Poland, the sixth largest country by population in Europe (38 million), has been struggling with a declining population for more than 20 years

Ageing population

Thanks to better medicine and living conditions, the average life expectancy in developed countries continues to rise. Professor Lynda Grattan of The London Business School expects 50% of people born today to live until they are 100 years old.

But as a consequence people born in 1998 will have to work much longer – many into their 80s. The consequences of this are already being experience in Japan which has the world’s most ageing population.

In Japan, 39% of people are expected to be over 65 by 2050 - a figure currently at 27%. The impact on healthcare and pensions is immense. The current percentage of people over 65 in the US is 15%, UK at 18%, France at 19%, Germany at 21% and Italy at 23%; but all are increasing significantly.

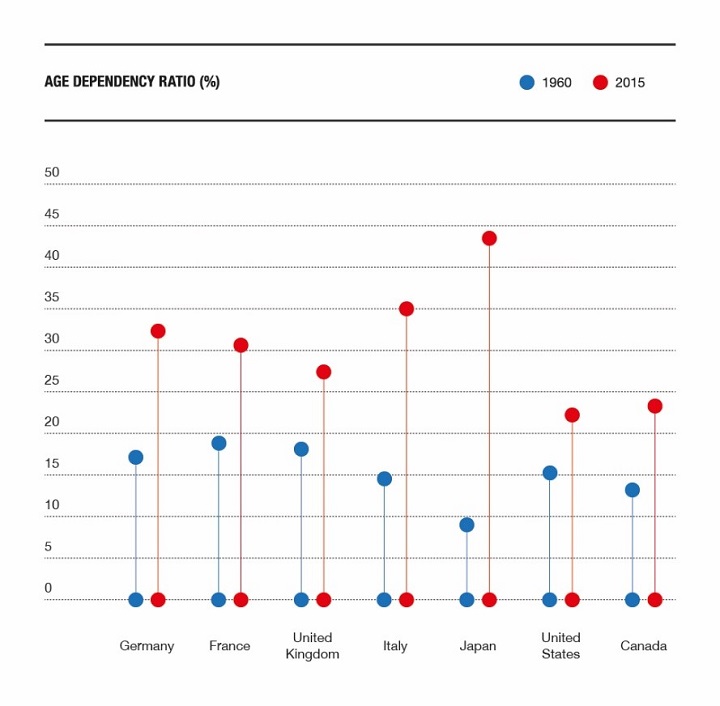

All of the G7 countries are facing increasing age dependency ratios – the number of elderly people that need to be sustained by the wealth generated by the working population. Since the 1960s there have been very large increases, but this will be made significantly worse in Japan, Germany and Italy compounded by low birth rates.

Graph 1

Changes in Age Dependency 1960-2015 of G7 Economies (elderly people as % of working population)

International migrants tend to include a larger proportion of working-age persons compared to the overall population, and so positive net migration can contribute to reducing old-age dependency ratios as well as driving up birth rate as has been see in Germany. However, international migration cannot reverse, or halt, the long term trend towards population ageing. Even if current migration patterns continue, all major countries are projected to have significantly higher old-age dependency ratios in 2050.

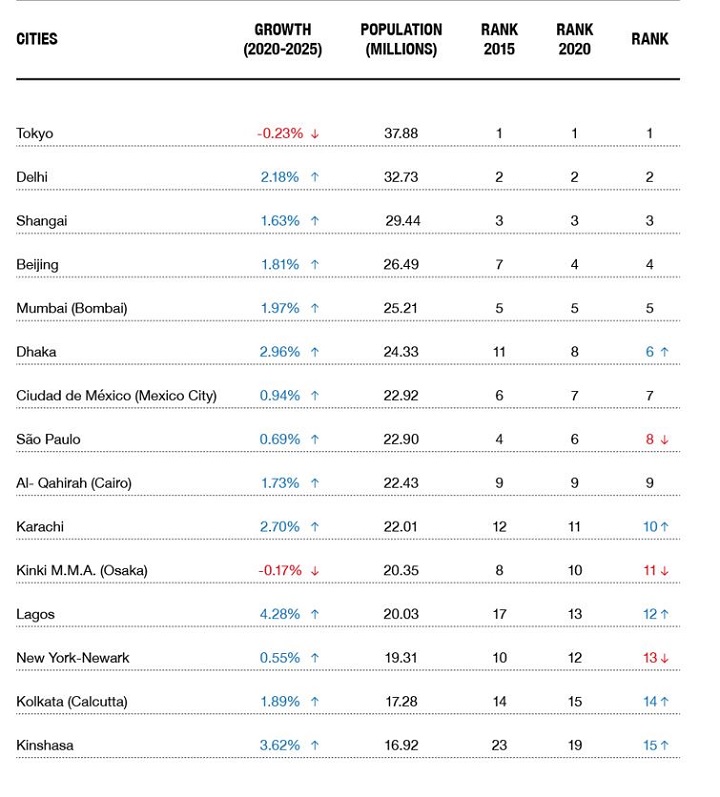

Table 1 – World’s largest cities and growth rates over next 5 years

Rise of the Cities

Until recently, we have seen counter-urbanisation in Europe's more developed countries and across the US.

The increase in car ownership over the last 50 years has meant that people could choose to live further away from city centres and away from crowds, crime and congestion.

Business parks sprung up in peripheral locations to ease the commute for employees and benefit from lower cost locations. However, in the last five years, this latter trend has reversed.

Younger people in particular now prefer to live in the city and businesses, eager to attract talent, have followed them back to the Central Business Districts (CBD). This trend means we are seeing cities like London, Paris, New York, Los Angles and Houston growing in population as young professional migrate back into the city centres.

London is forecast to growth by 2.5m between now and 2031 - a phenomenal growth of 16% when it has been static for many years. This has also been driven by a recognition that cities are economically and environmentally more sustainable than mass suburban sprawls.

There is extensive research on the wellbeing and health benefits of cities where infrastructure allows people to easily walk and cycle compared to a car-dependent population.

Many European cities such as Copenhagen are leading the way in creating truly sustainable and healthy places to work, shop and live. Urbanisation has also been fuelled by the desire of young people to work and live in cities, persuading corporates to return to the city centres to capitalise on this new breed of young 'city-centric' talent.

In Asia and Latin America, we have seen the rapid growth of cities as people have migrated from rural areas into urban areas in search of opportunities and wealth.

The trend has been so strong that we are seeing the rise of new super-cities with enormous populations emerging, but lacking the necessary infrastructure.

Anybody who has witnessed the apparent chaos of some of the faster growing super cities such as Dhaka in Bangladesh, Karachi in Pakistan or Lagos in Nigeria, will surely wonder how these cities cope without the basic infrastructure that sustains traditional developed cities.

And we will see more of these in the future; it is forecast that the number of mega-cities with populations of over 10 million will rise from 28 to 41 by 2030. Given that only one of these cities will be in Europe that demonstrates the shift of power that is being transferred from North to South globally.

Impact on the global economy

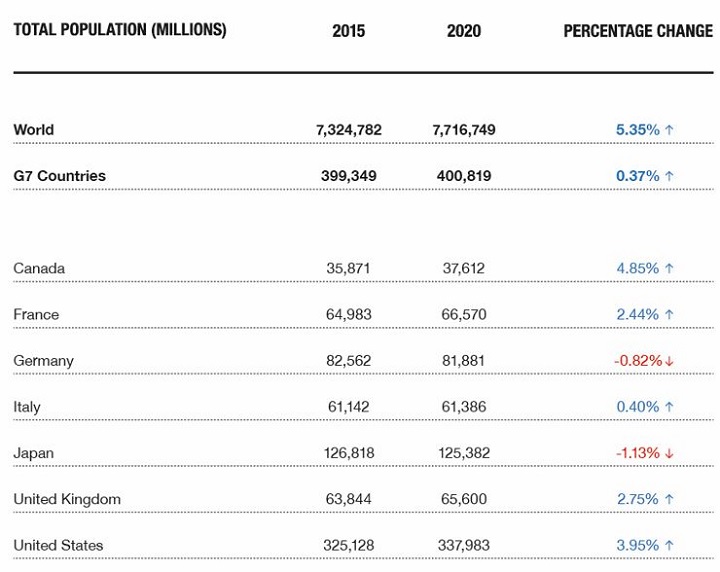

The overall impact of low birth rate and economic migration on the Global economy is reinforced by table 2 below which shows population growth for G7 countries. You can see Japan, Germany and Italy are all negative and given population size has a very strong correlation with economic growth this is indeed very concerning.

Table 2 - Population growth 2015-20 (source Oxford Economics)

Clearly countries like China and India are still growing significantly through population growth and enhanced productivity, driving GDP growth of 6% or more. Businesses clearly recognise this and are investing heavily into these markets, often turning around capability that was developed as a cheap production facility to service the G7 markets' domestic demand.

But the challenges in the developed world are a significant long term political and economic risk that will impact businesses operating in these markets. The population implosion risks for Germany, Japan and Italy as well as many smaller developed countries are significant, and together with increasing old-age dependency ratios in all G7 countries raises many fundamental questions, especially at a time of low growth and high debt.

If you'd like to discuss any of the points raised in this article and how they may affect your business please email me.

Knight Frank's EMEA Strategic Consulting team works with large and small business helping them to align property to business goals and objectives and, in turn, making them more competitive and fast moving.