The potential of rewilding: an interview with the owners of the Knepp Castle Estate

Andrew Shirley, Head of Rural Research at Knight Frank, talks to rewilding champions Charlie Burrell and Isabella Tree

5 minutes to read

According to the latest instalment of Knight Frank’s Rural Sentiment Survey, putting more land into conservation schemes is one of the top five ways that farmers and landowners plan to adapt to life after Brexit and cope with the other challenges facing agriculture.

Rewilding is one option and a bit of a buzzword at the moment. To get the lowdown from some early adopters I paid a visit to the Knepp Estate in Sussex to meet Charlie Burrell and his wife Isabella Tree. The following is an extract from my interview with them featured in the 2019 edition of The Rural Report.

The Knepp Castle Estate

I’m standing in the middle of the 1,400-hectare Knepp Castle Estate, not far from Horsham in West Sussex. And yet it still seems a million miles away from any farm or estate I’ve visited in the UK before.

In her recently published book about the estate, Wilding, the return of nature to a British farm – one of the Smithsonian’s top ten science books for 2018 – Isabella recounts numerous such moments evoking memories of other places and times.

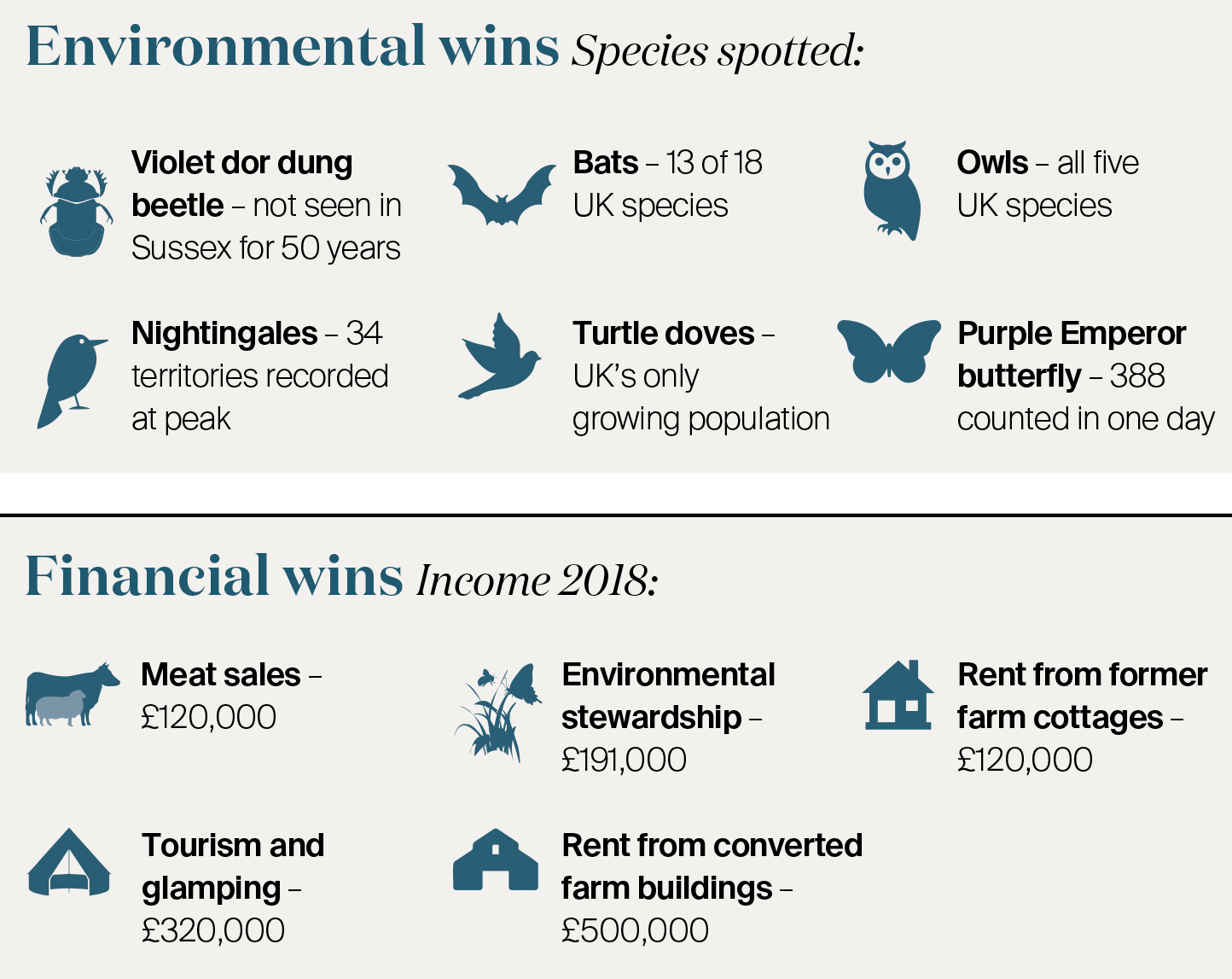

"The return of the warbling coo of the turtle dove, almost extinct in the UK; a vivid haze of resurgent Purple Emperor butterflies; and, perhaps most evocatively of all, the complex and staccato conversations of nightingales once again proudly proclaiming their territories to each other."

It feels that something revolutionary is afoot here. The reviews on the back of Isabella’s book – “One of the landmark ecological books of the decade,” cries The Sunday Times; “Hugely important,” implores The Guardian – certainly bear that out.

The fact that some of Knight Frank’s biggest landowning clients were keen to accompany me on my visit also confirms that things are done differently, very differently, at Knepp. And they’re not alone.

“Last year we were visited by the owners of a million acres and this year it will be a million more,” confirms Charlie.

Brexit conundrum

Their curiosity is driven in part by the need to solve the conundrum currently facing many of the UK’s farm and estate owners: how to keep their land profitable after Brexit when area-based subsidy payments will gradually fade away.

The transformation of Knepp seems to offer one of the answers.

But for Charlie and Isabella, it wasn’t a single defining event that catalysed the creation of this seemingly foreign landscape surrounding me.

Rather, it was the gradual realisation at the tail end of the last century that farming grade 3 and 4 land on 320 metres of Sussex clay, despite their best efforts to modernise and become more efficient, just wasn’t profitable.

The estate’s dairy farms were the first to go. Then in-hand arable farming bit the dust, machinery auctioned off to be replaced by a contractor. The Repton parkland ploughed up during the Dig for Victory campaign of the Second World War was restored to permanent pasture, and fallow deer were reintroduced.

"The estate began to breathe again," recalls Isabella. "And as the land began to relax, so did we."

Radical surgery

But it wasn’t enough. More radical surgery was required to satisfy the Burrell’s growing hunger to be surrounded by nature and wild spaces.

A visit to Holland’s pioneering – and controversial – 6,000-hectare Oostvaardersplassen (OVP) nature reserve where grazing animals live, roam, reproduce and die freely with minimal human intervention, all the while reshaping the landscape in unexpected ways, inspired them to look again at Knepp’s potential in a completely new light. The decision to rewild had been taken.

“Until recently the consensus among ecologists was that land left to its own devices would eventually revert back to closed canopy woodland, but the impact of large herbivores at OVP has turned that theory on its head,” says Charlie.

Wild boar and bison

Eager to capitalise on the interest stirred up by these findings, he submitted an ambitious “letter of intent” to establish a biodiverse wilderness area involving bison, beavers and wild boar to English Nature.

Unsurprisingly, this was considered too much too soon, particularly on an estate criss-crossed with public rights of way.

But the Burrells persevered, eventually getting the entire estate accepted into the Higher Level Stewardship scheme.

They gradually substituted the wilder animals on their original wish list with more acceptable breeds – old English Longhorn cattle, Exmoor ponies, Tamworth pigs and fallow and red deer.

These can roam freely with minimal human intervention, replicating the different feeding habits of the original herbivores that inhabited the Sussex Weald without scaring ramblers and dog walkers.

The results in little more than a decade have been phenomenal, both environmentally and financially.

Tourism potential

Sales of the estate’s totally organic and free-range meat generate a significant income, while visitors flock to go on safaris or stay at Knepp’s campsite and in its glamping tents and treehouses.

“We are fully booked for the whole season,” says Charlie. “Our profit margins are 30 to 40%. You can’t get that from farming.”

And, of course, there is the landscape, redolent to me of African savannah.

Left to its own devices, it has changed beyond recognition with dense scrub and thicket replacing crops and manicured grassland, while hedges billow out into 30-metre wildlife havens.

knepp wildland 25.6.18 neil hulme small.jpg)

We have purposefully not tried to recreate habitats for the benefit of specific species like nightingales, but to let nature take its own course and see what returns of its own accord,” says Charlie. “The results have been beyond what we could ever have hoped for.” Read the full interview in The Rural Report for the Burrells’ response to rewilding’s critics.

To find out more about Knepp visit knepp.co.uk

Wilding, the return of nature to a British farm by Isabella Tree has been published in paperback.