The Alphabet Game

It is now beyond doubt that the UK and Global economies are entering a recession triggered by the global pandemic Covid-19.

4 minutes to read

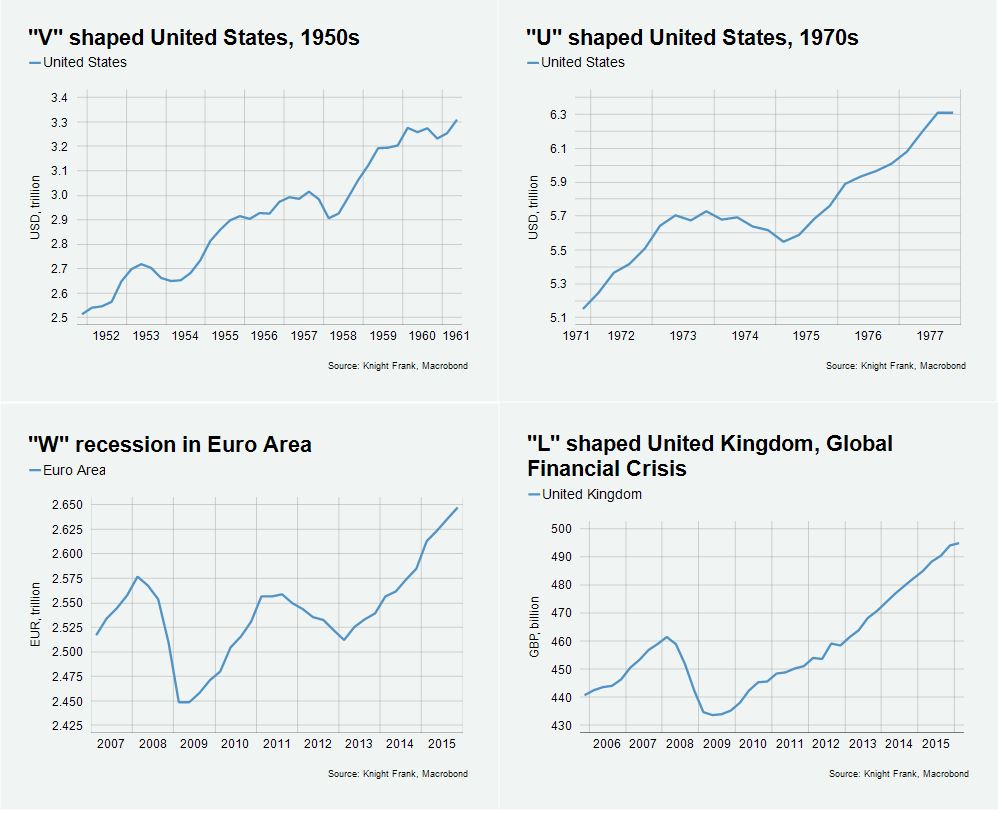

This was reinforced yesterday as the latest Purchasing Manager Indices (PMIs) for the Eurozone and the UK plunged to historic lows. The focus has now shifted not to when, but how long and what shape the downturn will take - a “U”, “W”, “L” or the much preferred ‘”V” shape.

The best case is a “V” shaped recession – a quick decline in activity followed by a quick and strong recovery, usually spurred by increased consumer spending. The two recessions in the US in the 1950s provide examples of this: in both cases it took around a year for GDP to return. Unemployment went from 2.5% to a height of 6.1% before receding again.

The “U” shape is characterised by activity declining gradually, staying low and then rising steadily over time - typically around 12 to 24 months. Simon Johnson, former chief economist for the International Monetary Fund, described a U-shaped recession like a bathtub. “You go in. You stay in. The sides are slippery. You know, maybe there’s some bumpy stuff in the bottom, but you don’t come out of the bathtub for a long time.” In the US in the 70s, for example, it took two years for GDP to return to pre-recession and unemployment went from 4.6% to 9%.

The “W”, or double-dip recession, is a sharp decline, recovery and then decline again, before recovering a final time. The most recent example being the Eurozone economy in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and debt crisis in the 2000s - it took the Eurozone economy seven years to return to the Q1 2008 level of GDP. Unemployment went from 7.3% to a height of 12.1%.

The “L” Shaped recession can be the most dramatic, characterised by a sharp steep decline in activity and a very slow recovery period. It can take up to a decade to return to normal. Looking at the Global Financial Crisis, the UK economy took 5 years to return to the GDP level seen at the beginning of 2008. Unemployment went from a pre-crisis level of 5.2% to a peak of 8.5% in 2011 – it returned to 5.2% in 2015. The deepest decline annual decline in GDP was in Q1 2009, where year-on-year GDP was down 5.8%.

Partly as a result of the social distancing measures being put in place to limit the spread of Covid-19, the latest UK economic forecasts indicate GDP will fall this year by between 1.4% and 7%. However, given the fiscal and monetary response put in place by the government and Bank of England, many economists now expect the unemployment rate to hold between 4% and 6%. This would imply only a moderate rise from the 3.9% recorded in December 2019. Similarly, GDP is expected to rebound in 2021, with forecast growth ranging between 1.7% and 8.5%.

Global GDP is likely to either flatline this year or fall by as much as 1% - double the decline seen in 2009. However, economic forecasters predict a strong rebound of between 4.4% and 7.3% growth in 2021, better than the 5.4% after the GFC.

Early indications from China show that industrial production is rebounding first, while consumer spending is recovering at a slower rate. Forecasters main assumptions are that most economies will return to their pre-crisis path of GDP within a couple of years, but this has some upside and downside risks (below).

Upside risks

- Antibody tests becoming widely available would enable a faster return to economic activity

- Widespread testing to contain – for example this town in Italy where no new cases have been reported

- Sizable fiscal and monetary stimulus supports employment globally and allows for a consumer-led recovery - this is the quickest and normally largest way in which growth rebounds

Downside risks

- Quarantine measures last for months in developed and emerging economies creating long lasting effects

- Even as quarantine measures lift within countries, given the staggered spread globally, there will be severely restricted global travel to avoid imported cases

- Lifting quarantine too early leads to a larger second peak, extending the economic impact

- There is a broader financial crisis with many corporate debt defaults

- The fiscal measures in place do not curtail widespread unemployment, lessening the likelihood of a consumer led recovery

https://www.ft.com/content/0dba7ea8-6713-11ea-800d-da70cff6e4d3