The countdown to Brexit from a farming perspective

With less than a year until the UK leaves the EU, Andrew Shirley takes a step-by-step look at what we know about the Brexit journey so far.

8 minutes to read

On 29 March 2019 at 11pm the UK, after almost five decades of membership, will leave the EU. Our departure date is set in stone.

Cue rejoicing, wailing or indifference. But from a farming perspective, regardless of what your persuasion on Brexit happens to be, it does beg the question: what happens next on the journey and what will the destination be like?

Unhelpfully, despite its proximity, we are far from a definitive answer to those questions. Over the next few pages we go through the various legs of the Brexit itinerary and examine what we know so far about each.

Departure lounge

The one-way ticket has been issued, but as the farming industry waits for the departure date how prepared is it for the voyage out of the EU? In many ways, not at all, but financially things could be worse.

The government’s recently released first estimate of Total Income from Farming (TIFF) in the UK for 2017 shows a marked upturn in the fortunes of farming.

TIFF amounted to just over £5.7bn last year, a significant improvement on the £4.1bn recorded in 2016. Exchange rates and slightly perkier commodity markets helped, but, according to Defra, farming productivity saw a timely rise, up by 2.9% to its highest-ever level.

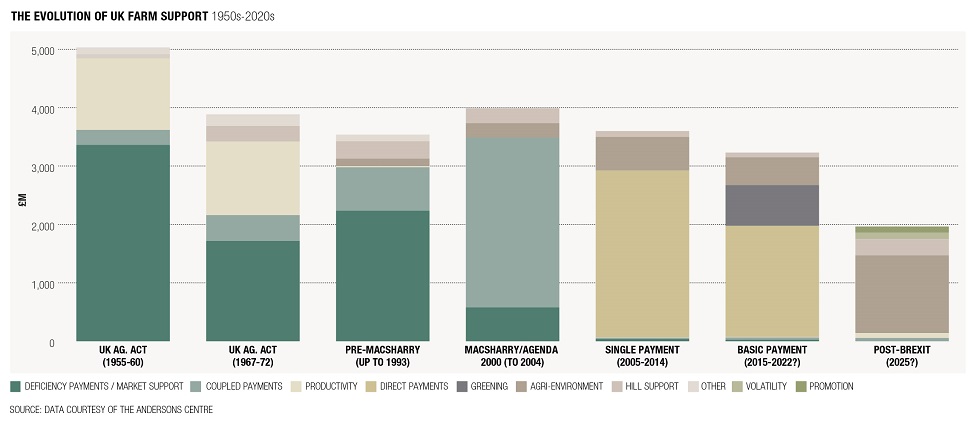

Outputs increased in volume by 3.6%, while inputs rose by just 0.7%. However, it’s worth noting that farm support payments under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) still accounted for 57% of TIFF.

What those repayments will potentially be replaced with was covered in a pre-Brexit guidebook provided earlier this year courtesy of Defra Secretary of State Michael Gove. The colour mentioned in the title Health and Harmony: the future for food, farming and the environment in a Green Brexit, gives a clear hint as to his favoured direction of travel.

Whether the 44,000 reader reviews of the document will agree with the minister’s suggestions remains to be seen. But it seems quite likely many will, given that most of them, according to press reports, were from single issue environmental pressure groups rather than working farmers.

Once collated, the responses will then feed into a new Agricultural Bill set to be published later this year. The bill will create the enabling legislation that will pave the way for the environmental land management system (ELMS) that will replace the EU’s CAP-based schemes in England.

Take-off

One thing that has become clear is that our flight from the EU is not going to be a quick one – we are going to remain in European airspace for quite some time. Having realised that it was going to be impossible to finalise all the details of Brexit, including a new EU-UK trade deal, by March 2019, negotiators have agreed on an “implementation period” that is currently set to last until 31 December 2020.

This will overlap with a longer “agricultural transition” period that will see farming businesses gradually weaned off their CAP area-based subsidies and switched to the new ELMS mentioned earlier. This could last until 2025 or even longer, depending on feedback to Health and Harmony.

Mr Gove has committed to pay UK farmers the equivalent of what they’ve been getting from Brussels until the scheduled end of the current parliament in 2022, but the weaning process will start in 2019. This will involve capping of Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) payments to release funds for creating pilot ELMS projects.

Exactly how this will happen will again depend on the outcome of the Health and Harmony consultation, but Mr Gove’s initial favoured options seems to involve slicing the payments of the biggest BPS recipients the hardest, based on the assumption that they are the most efficient producers and can take the hit.

Lobby groups such as the NFU and CLA claim, however, that is not always the case and that a flat-rate cut applied to all recipients would be much fairer and ensure everybody starts to plan for Brexit.

Whichever option is chosen, further cuts will be applied after several years or annually until the BPS element of support is cut to zero. In terms of environmental payments a simplified version of the existing Countryside Stewardship Scheme will remain in place until ELMS is ready to be introduced.

Arguably the most contentious area of Brexit to be thrashed out – in both Brussels and Westminster – is our future trading relationship with Europe. The EU is our biggest trading partner so we don’t want to lose our privileged access to that market, but at the same time we want to be able to strike deals with the rest of the world.

The requirement to maintain an open border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic adds a severe degree of turbulence. At the time of writing, Theresa May is suggesting two options.

One is a “customs partnership” where the UK basically acts on behalf of the EU when dealing with imports from the rest of the world. The other, known as maximum facilitation or max-fac, aims to create as frictionless a customs border as possible, rather than to remove it altogether.

Both are untested and will rely on IT systems that don’t yet exist. The EU is keen on neither and Brexiteers are unhappy because they feel it still gives the EU too much control. Another option being touted again is to join Norway in the European Economic Area (EEA), but again this crosses a number of red lines.

Michael Haverty, a Senior Agricultural Economist with The Andersons Centre, feels a bespoke association agreement is probably the likeliest outcome. This model has already been used between the EU and Ukraine and Georgia. “It offers the most flexibility and while a deal would still have oversight by the European Court of Justice on some issues, that could be considered a price worth paying by more pragmatic Brexiteers.”

Although some claim it doesn’t really matter if we can’t reach an agreement and the UK will be fine trading under World Trade Organisation terms, most models suggest it would be very bad news for those farming sectors, particularly the sheep industry, that are reliant on export markets.

Hopefully pragmatism on both sides will prevail.

Touch down

We’ve finally landed, the EU is behind us, the transition and implementation periods are over. What does farm support look like? As described in Health and Harmony it is very green, the buzzwords are “public money for public goods”, “natural capital”, “ecosystem services” and worryingly to some “the polluter pays”.

Farmers will be rewarded for delivering things such as improved soil heath, water and air quality, increased biodiversity, climate change mitigation, safeguarding beauty and heritage, and access to the countryside, while potentially having to bear the costs of environmental damage, however that is measured.

The mechanisms for all of this have yet to be created. Simplest would be an enhanced version of existing environmental stewardship schemes bankrolled by the government.

Michael Gove, however, led by proposals from environmental groups and the government’s own Natural Capital Committee, seems more interested in an ambitious market-led system where the natural capital and ecosystem services mentioned above are paid for by businesses, utilities companies, environmental NGOs and even private philanthropists, as well as government.

Potentially delivered on a water catchment area basis, such schemes could favour more marginal areas. The principle sounds simple, the delivery more complex. The onus could be more on landowners to identify what public goods they can deliver and establish partnerships with those prepared to pay for them.

And trade? This is arguably where a change in scenery will take longest to achieve. Organisations like AHDB and individual businesses have put a huge amount of effort into opening up new markets especially in Asia, and they have been successful – to a certain extent. In financial terms though, the volumes are still relatively small.

Comprehensive free trade agreements can take many years to conclude, agriculture is often a sticking point or excluded altogether, and international completion is fierce. Buying and selling from your nearest neighbours is usually more convenient.

Trip adviser

Looking to the long-term even some of those who wanted to remain in the EU do admit that leaving it does hold out a potentially exciting future for farming in Britain. But some very tricky questions remain.

Does Defra, for example, fully understand how difficult this journey could be for the sizeable proportion of farmers – big and small – whoaren’t currently profitable on a regular basis without farm support payments? Much more space is given to the environment in Health and Harmony than profitable farming.

And how realistic is it to deliver a fully functioning replacement for CAP in a relatively short period of time? The models proposed seem elegant on paper, but in reality are hugely ambitious requiring complex new technology systems and human support to make them function efficiently. Not something any government has a good track record on.

Last, but not least, trade. If no trade deal with Europe can be reached by the end of the “implementation period”, the farming sector will potentially be one of the hardest hit. Without Brussels to hide behind, the buck will stop with the government. Taking back control will also mean taking back responsibility.

For landowners and farmers, nature will need to be viewed as another crop to be farmed for profit, while every asset whether land, buildings or houses will need to be sweated like never before.

Get ready for take-off. It could be a bumpy ride.

This article appears in 2018's The Rural Report - a unique guide to the issues that matter to landowners.